Innovate Articles

Interstellar IP: Unusual Inventions for Manipulating Spacetime, Constructively Reduced to Practice

Elijah E. Cocks

“The filing of a patent application serves as conception and constructive reduction to practice of the subject matter described in the application. Thus, the inventor need not provide evidence of either conception or actual reduction to practice when relying on the content of the patent application.”

- Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP) 2138.05

Introduction

Bright ideas are as plentiful and varied as the stars in our universe. But under patent law, a conceived idea does not become an invention for which intellectual property (IP) protection may be sought until it is reduced to practice. Long gone are the days when the U.S. Patent Office required that a working model of an invention be submitted with every patent application. It is not required to actually build an invention to reduce it to practice. Instead, the filing of a patent application itself serves as a “constructive” reduction to practice of the disclosed invention. This, of course, does not mean these inventions are necessarily patentable. Whether patentable inventions or not, this article considers some examples of unusual patent-attempted concepts concerning spacetime, black holes, wormholes and more, as constructively reduced to practice by their filing as patent applications that has provided their disclosure in the public record of the galaxy forevermore.[1]

A Brief History of Constructive Reduction to Practice

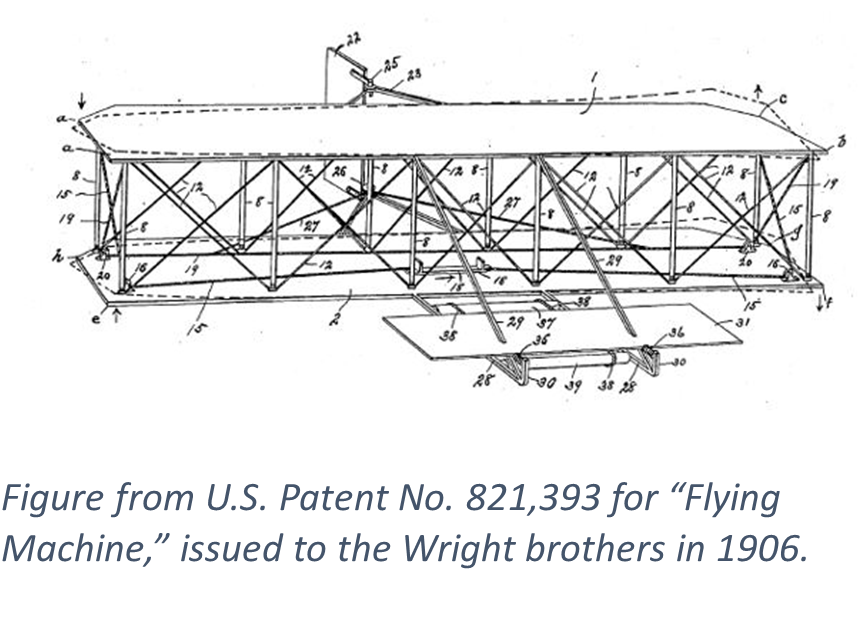

Under U.S. patent law, an invention is an idea that has been conceived and reduced to practice, at which time patent rights may be sought for that invention. From 1790-1880, the U.S. Patent Office required that an applicant submit a working model of an invention with a patent application.[2] After 1880, the Patent Office required working models only for purported perpetual motion machines and “flying machines which have no balloon attachment.”[3] The requirement for a model of such a flying machine, and the associated refusal to otherwise consider patents to that type of invention, was dropped in the early 1900s, and U.S. Patent No. 821,393, entitled “Flying Machine,” was issued to the Wright brothers in 1906.[4] The requirement for a working model of a perpetual motion machine remains to this day.[5]

The legal concept that a patent could be applied for, and validly obtained, for an invention that was never actually made or performed and based only on embodiment in written description – a constructive reduction to practice – emerged in the mid-to-late 1800s.[6] This was seemingly first recognized by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1878 in Bates v. Coe,[7] a patent infringement case involving drilling machines, and explicitly stated a decade later in The Telephone Cases,[8] a series of patent dispute cases before the Supreme Court involving Alexander Graham Bell and the invention of the telephone:

It is quite true that when Bell applied for his patent, he had never transmitted telegraphically spoken words so that they could be distinctly heard and understood at the receiving end of his line; but in his specification he did describe accurately, and with admirable clearness, his process… The law does not require that a discoverer or inventor, in order to get a patent for a process, must have succeeded in bringing his art to the highest degree of perfection; it is enough if he describes his method with sufficient clearness and precision to enable those skilled in the matter to understand what the process is, and if he points out some practicable way of putting it into operation. This Bell did.

Over the subsequent decades, the legal sufficiency of constructive reduction to practice for establishing a patent application filing date for an invention to be examined for patentability has become embedded in the U.S. patent system. The Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP) from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) summarizes recent case law and USPTO patent examination rules and practices concerning reduction to practice of an invention. The filing of a patent application serves as conception and constructive reduction to practice of the described subject matter. An inventor need not provide evidence of either conception or actual reduction to practice when relying on the content of the patent application.[9]

None of this, however, means the invention is necessarily patentable. Although a patent examiner may not assess the technical sufficiency of the filed specification itself for purposes of constructive reduction to practice and the accorded filing date of the patent application, the examiner can and will examine the claims of the patent application for patentability, including for novelty and nonobviousness as well as for utility and enablement. An examiner may reject claims as lacking credible utility and enablement under 35 U.S.C. 101 and 112 on the basis that the claims contain subject matter that was not described in the specification in such a way as to reasonably convey that the inventor had possession of the claimed invention at the time it was filed or that would enable one of ordinary skill in the art to make and/or use the claimed invention.[10] An applicant may argue against these rejections, submit evidence to suggest that one of ordinary skill in the art would have a legitimate basis to understand the claimed invention, and even appeal the rejections to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board and the courts in an effort to secure a patent for the claimed invention.

Regardless of the result of the patent prosecution, the fact that an applicant has filed a patent application for a conceived and constructively-reduced-to-practice invention is undisputed. The patent application, once published, then enters the permanent public record, disclosing to the world all the subject matter therein, whether or not patentable or even operable at the time it was filed, and containing one or more inventions that may reach to the stars themselves. Let us consider a few such exotic examples and their examination fates at the USPTO.

STAR-SPACE IP | PIE CAPS RATS

Black holes and wormholes. Warp drives and time travel. The spacetime-bending subject matter of the following patent applications may be more familiar as plot devices in science fiction movies than as seen in practical reality. But whether science fiction or science ahead of their times, the concepts and constructive reduction to practice of the inventions of these filed patent applications, published as U.S. patent application publications, have been disclosed for public review and consideration in the USPTO patent databases.

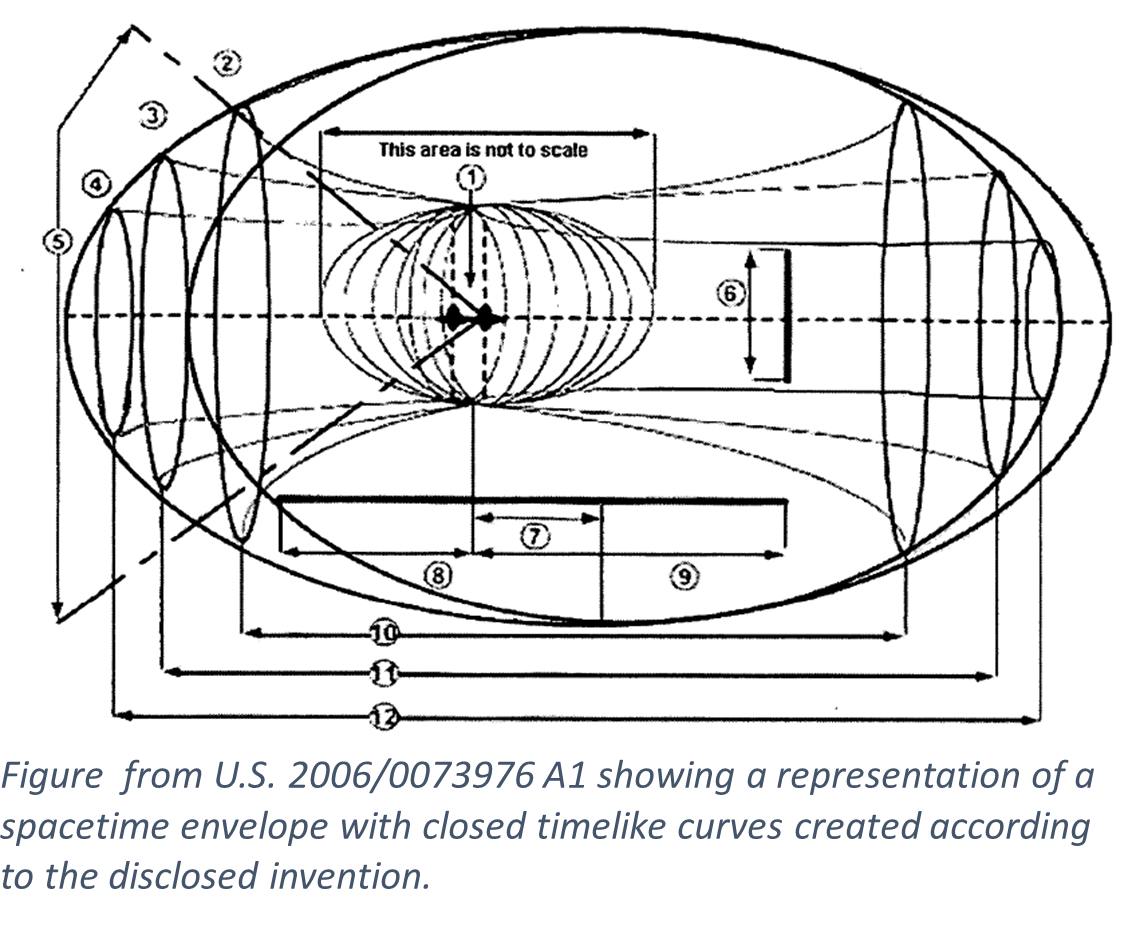

U.S. 2006/0073976 A1: Method of Gravity Distortion and Time Displacement

This patent application, filed in 2004 and published in 2006, relates to the use of time displacement devices which operate by modification of gravitational fields. The specification provides disclosure concerning multiple topics including, inter alia, Quantum Gravity, Graviton Force Characteristics, Quintessence and Black Holes, and Closed Timelike Curves, stating “With this understanding of space-time, matter and the forces of Nature, and in particular gravity, it is possible to demonstrate that the modification of gravitational fields, and in turn the warping of space-time, can be technically readily achieved.”

The claims of the application were initially rejected by the patent examiner as being inoperative and thereby lacking utility, as well as failing to comply with the enablement requirement. Despite a lengthy response by the applicant including claim amendments made to better define the invention and hundreds of pages of argument and submitted explanatory information, the examiner maintained the claim rejections, and the application went abandoned in 2008.[11]

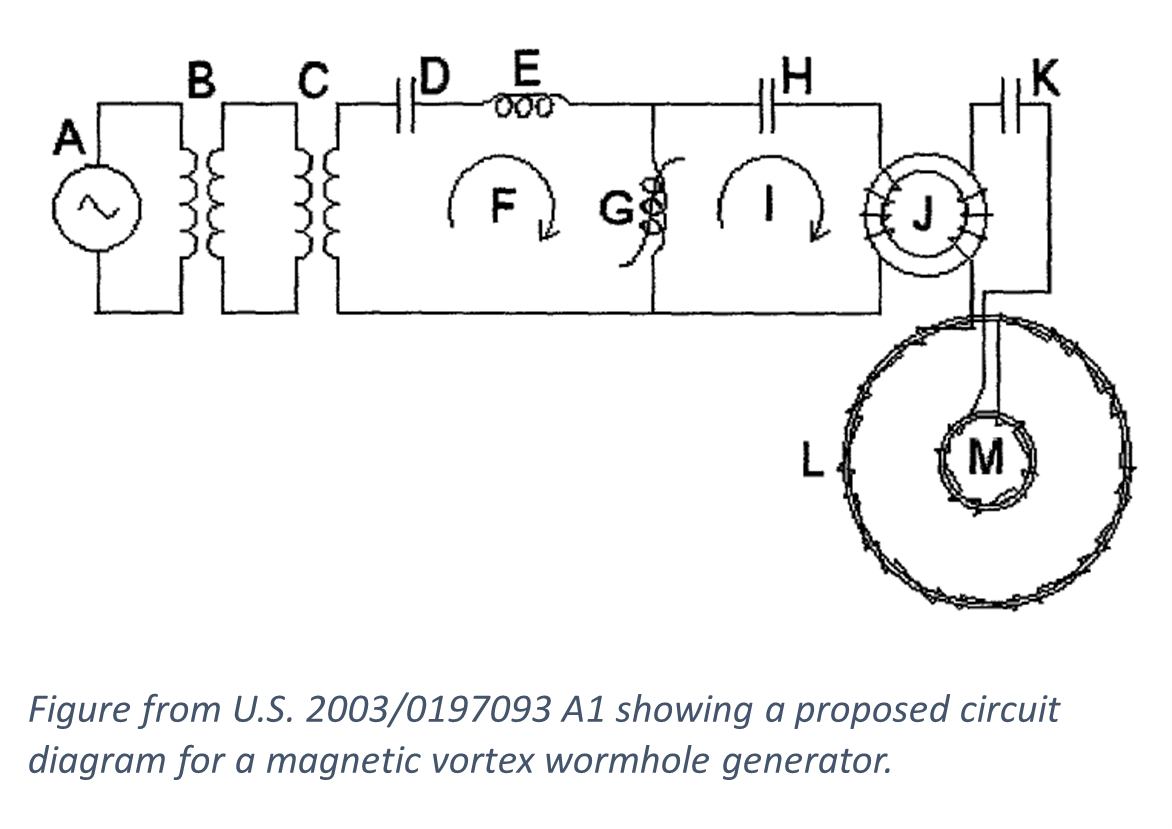

U.S. 2003/0197093 A1: Magnetic vortex wormhole generator; and

U.S. 2006/0071122 A1: Full Body Teleportation System

These two subject-matter-related patent applications, filed in 2002 and 2004 and published in 2003 and 2006, respectively, disclose systems and uses for a magnetic vortex wormhole generator that creates “spikes of negative mass” that distort spacetime and open a wormhole into hyperspace. The earlier-filed patent application discloses concepts for the wormhole generator for such applications as enabling spacecraft to travel light years by moving through hyperspace. The later-filed patent application discloses “a pulsed gravitational wave wormhole generator system that teleports a human being through hyperspace from one location to another.”

In each case, the claims of these applications were rejected as lacking utility, with the examiner concluding: “The invention is not supported by a credible utility or well established utility because the claims call for the generation of gravitational waves and the interacting of the waves with hyperspace… The existence of hyperspace is not well proven or shown to exist in accordance with credible science and physics.” The applications went abandoned in 2003 and 2006, respectively.[12],[13]

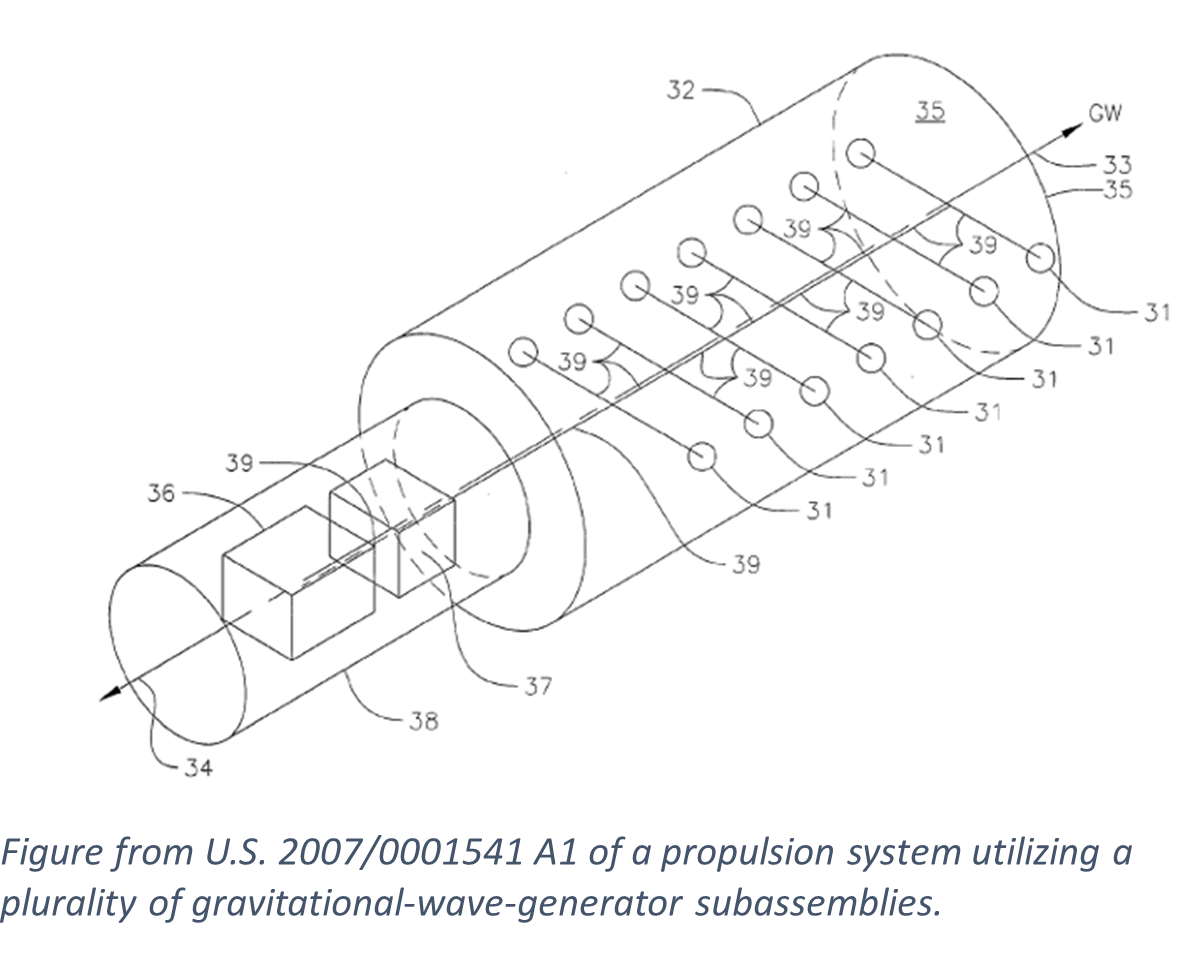

U.S. 2007/0001541 A1: Gravitational Wave Propulsion

This patent application discloses a gravitational wave generator device that can be used to propel an object by changing the gravitational field nearby the object to urge it in a preferred direction. The stated concept of the invention is to “simulate or emulate [gravitational waves] generated by gravitational-force, extensive energizable celestial systems (orbiting binary stars, asymmetrical star explosions, merger of black holes, etc) by the use of compact electromagnetic -or nuclear-force energizable systems.”

The claims of the patent application were rejected by the examiner on grounds of lack of enablement, citing undue experimentation required for making and using the claimed propulsion system. In further rejecting the claims as being inoperative and lacking utility, the examiner noted that under applicant’s proposed focusing of gravitational waves to create a spacetime singularity, it was “not clear how any propelled object known at the present time could exist under such extreme conditions.” The examiner invited the applicant to furnish a working model of the invention to demonstrate its operability. The application went abandoned in 2008.[14]

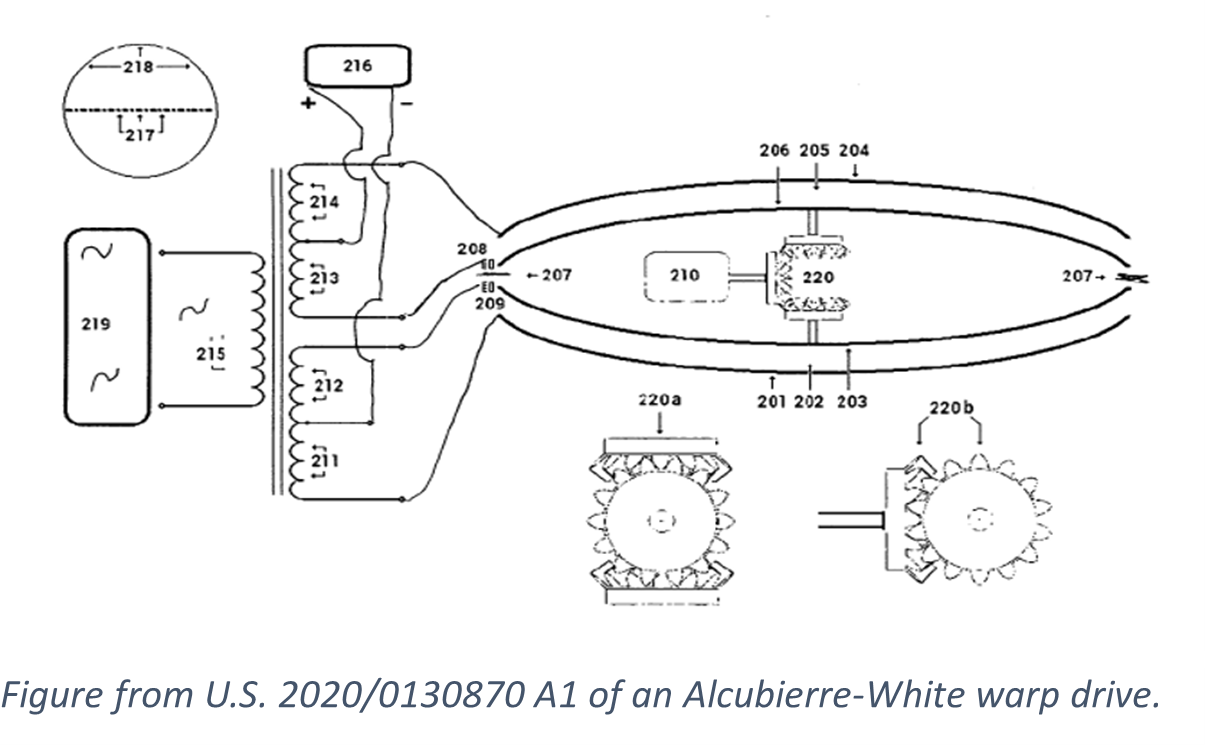

U.S. 2020/0130870 A1: Alcubierre-White Warp Drive Machine

Filed in 2018 and published in 2020, this patent application relates to propulsion by changing the metric of spacetime via manipulation of electric charges and of electric fields, disclosing use of a form of warp drive identified as Alcubierre-White that “softens space-time by rapidly oscillating energy and by using a ring structure of an oscillating mass.” It proposes using two Alcubierre gravitational walls to achieve a warp drive effect as means of propulsion while surrounding a space where passengers can travel.

The examiner rejected all claims on grounds of lacking utility and enablement, stating: “When a patent applicant presents an application describing an invention that contradicts known scientific principles, or relies on previously undiscovered scientific phenomenon, the burden is on the examiner simply to point out this fact to the applicant. The burden shifts to applicant to demonstrate that his invention, as claimed, is either operable or does not violate said basic scientific principles, or those basic scientific principles are incorrect.” The examiner invited the applicant to furnish a working model of the invention to demonstrate its operability. The application went abandoned in 2021.[15]

Into the Cosmos

Millions and millions of U.S. patent application publications are stored in the USPTO patent databases. Many of these have become issued U.S. patents, granting IP rights to exclude others from making and using the claimed inventions, while many others have gone no further than simply being published documents. Regardless, however, these filed patent applications have disclosed the intellectual pursuits of many inventors, who have endeavored to constructively reduce their ideas to practice and thereby designate their ideas as inventions.

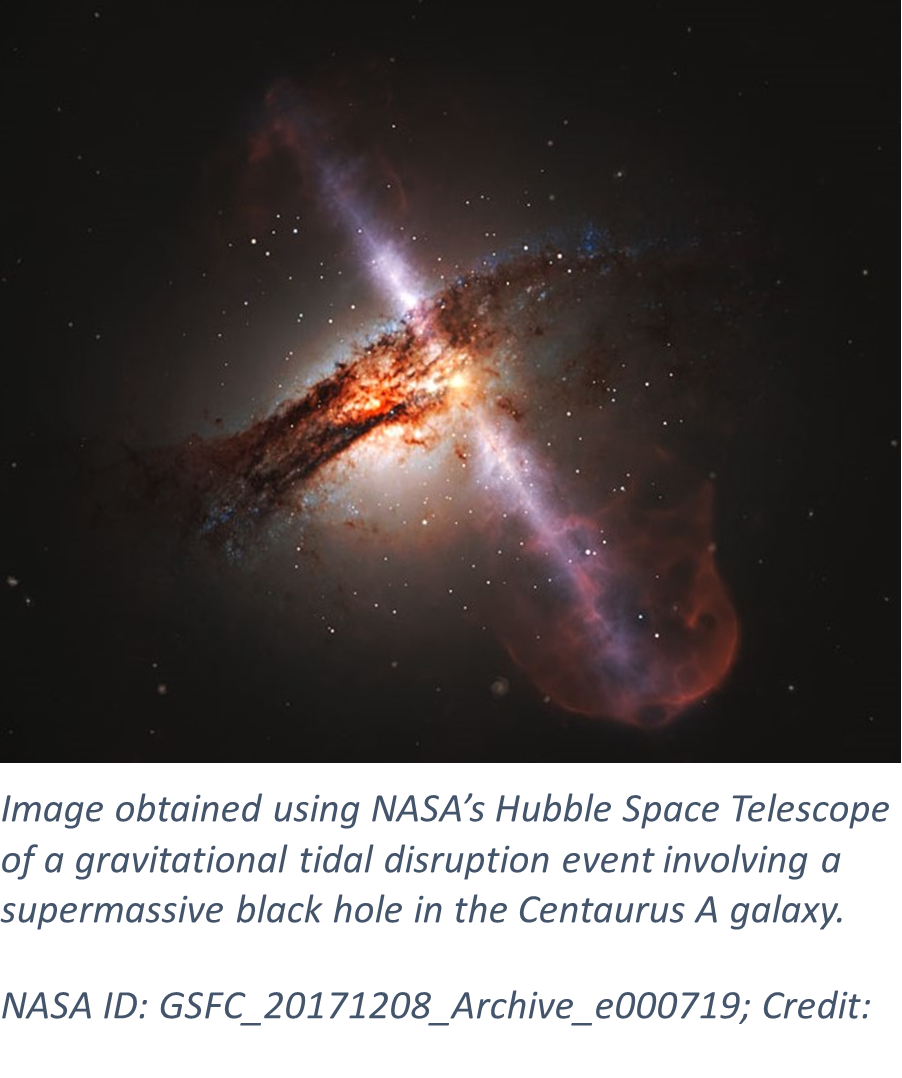

History has shown that what may initially be only wildly conceptual, standing unmade and unpracticed, can eventually become operable, observable and practical. From skepticism of “flying machines which have no balloon attachment” to the orbiting space telescopes observing the strange wonders of the cosmos,[16] the progress of technology has been known to allow that which first seems impossible to become reality. Meanwhile, the USPTO will still continue to wait to receive a working model of the first valid perpetual motion machine…

[1] Image NASA ID: PIA13168: images.nasa.gov/details/PIA13168. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

[2] The Patent Laws of the United States: together with Information for Persons Having Business to Transact at the Patent Office, Pamphlet, New York: Office of the Scientific American, 32 pp.: 12 (1849) (“No application can be examined until the fee for the patent is paid and the specification, model and drawings filed.”). Author’s collection.

[3] Victor J. Evans, How to Obtain a Patent: A Complete Compendium of Useful Information for Inventors, Brochure, 29th ed., Washington, D.C.: Victor J. Evans & Co., 80 pp.: 78-80 (1900) (“Many people are under the impression that a large sum of money has been offered by the United States Government for the solution to the problem of perpetual motion. Not only has no such offer ever been made, but on the contrary the Patent Office refuses to grant patents on devices of this character, and will not even consider an application for a patent claiming to solve this theory unless a full size working model is furnished. …The Patent Office also refuses to grant patents for airships or flying machines which have no balloon attachment, but contemplates creating power to provide for their own buoyancy.”). Author’s collection.

[4] U.S. Patent No. 821,393 to Orville and Wilbur Wright, “Flying Machine,” issued May 22, 1906: patents.google.com/patent/US821393.

[5] MPEP 608.03: Models, Exhibits, Specimens [R-08.2012] (“With the exception of cases involving perpetual motion, a model is not ordinarily required by the Office to demonstrate the operability of a device.”): www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s608.html#d0e50532.

[6] William Macomber, “Reduction to Practice of Patentable Inventions,” Univ. Penn. Law Review; Vol. 63, No. 5: 353-363 (March 1915): scholarship.law.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=7523&context=penn_law_review.

[7] Bates v. Coe, 98 U.S. 31, 39 (1878): supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/98/31/.

[8] The Telephone Cases, 126 U.S. 1, 535-536 (1888): supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/126/1/.

[9] MPEP 2138.05: Reduction to Practice [R-01.2024]: www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2138.html#d0e207753.

[10] MPEP 2107: Guidelines for Examination of Applications for Compliance with the Utility Requirement [R-11.2013]: www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2107.html.

[11] U.S. Patent Application Publication 2006/0073976 A1 to Pohlman, “Method of Gravity Distortion and Time Displacement,” pub. Apr. 6, 2006: patentcenter.uspto.gov/applications/10954767.

[12] U.S. Patent Application Publication 2003/0197093 A1 to St.Clair, “Magnetic vortex wormhole generator,” pub. Oct. 23, 2003: patentcenter.uspto.gov/applications/10127098.

[13] U.S. Patent Application Publication 2006/0071122 A1 to St.Clair, “Full Body Teleportation System,” pub. Apr. 6, 2006: patentcenter.uspto.gov/applications/10953212.

[14] U.S. Patent Application Publication 2007/0001541 A1 to Baker, JR., “Gravitational Wave Propulsion,” pub. Jan. 4, 2007: patentcenter.uspto.gov/applications/11173080.

[15] U.S. Patent Application Publication 2020/0130870 A1 to Suchard et al., “Alcubierre-White Warp Drive Machine,” pub. Apr. 30, 2020: patentcenter.uspto.gov/applications/16177167.

[16] Image NASA ID: GSFC_20171208_Archive_e000719: images.nasa.gov/details/GSFC_20171208_Archive_e000719. Credit: NASA/ESA/STScI.