In This Section

AI Regulation & Trade Secrets Protection – Do they conflict?

Written by Matthew D’Amore on June 30, 2025

AI Regulation & Trade Secrets Protection – Do they conflict?

Matthew D’Amore

The past year produced a flurry of state legislative efforts to address the risks associated with the increasing capabilities of artificial intelligence systems.[1] While generative AI systems like ChatGPT draw attention in public discourse, the enacted and proposed state laws reach other algorithmic systems whose use might present a risk to the public. At the same time, these efforts may present a risk to the trade secrets employed in developing and deploying the regulated AI systems.[2]

Below, this paper provides a brief overview of some of the principles behind these regulatory approaches, and then examines two – California’s AB-2013, the Generative Artificial Intelligence Training Data Transparency Act,[3] and Colorado’s SB-24-205, concerning consumer protections in interactions with artificial intelligence systems.[4]

Background

Algorithmic “artificial intelligence” tools with the power to process, learn from, and make decisions upon vast amounts of data have been around for years, with the recent generative and agentic AI systems as only the latest (and most public) iteration. For many years, however, the academic community has been concerned with the potential risk of such systems, whether from algorithmic bias, in the case of decision-making systems relating to employment or credit[5], or physical or monetary harm, in the case of financial, autonomous vehicle or health-related systems.[6]

AI regulatory efforts often rely on principles of transparency and explainability.[7] According to the Organization for Economic Development (OECD), which issued a widely discussed recommendation for governance, “transparency” can be understood as “disclosing when AI is being used (in a prediction, recommendation or decision, or that the user is interacting directly with an AI-powered agent, such as a chatbot).”[8] It can further include information concerning “how an AI system is developed, trained, operates, and deployed … so that consumers, for example, can make more informed choices.”[9] The OECD recognizes that transparency should not include source code and datasets themselves, which might be too complex to provide transparency and “may also be subject to intellectual property, including trade secrets.”[10] “Explainability,” on the other hand, “means enabling people affected by the outcome of an AI system to understand how it was arrived at.”[11]

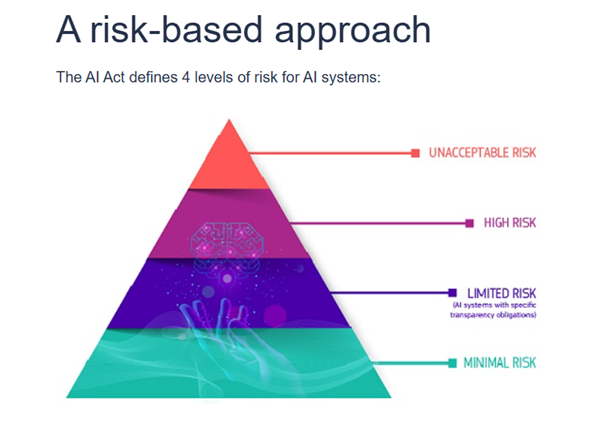

These efforts also involve a risk assessment necessary to determine which systems to cover. As Professor Margot Kaminski explains (and critiques), “Regulators have recently converged around using risk regulation to govern AI.”[12] The EU AI Act’s explanatory website provides an illustration:[13]

Under the EU framework, systems with “unacceptable risk” are prohibited, “high risk” systems are subject to a registration and risk management regime, while “limited risk” systems require some disclosures to the public under the principles of transparency and explainability discussed above.[14]

With this background in mind, we can turn to examining California and Colorado’s recent AI legislation, including how those laws intersect with trade secret protections for the systems they propose to regulate.

Colorado SB24-205

The Colorado AI Act (CAIA) follows many of the principles above, including a focus on “high-risk” systems, transparency requirements placed on developers and deployers, and mechanisms for accountability, while also providing some trade secret protections.[15] The CAIA is broadly directed to "Artificial Intelligence Systems", which mean “any machine-based system that, for any explicit or implicit objective, infers from the inputs the system receives how to generate outputs, including content, decisions, predictions, or recommendations, that can influence physical or virtual environments.” However, most of its provisions concern “High-Risk Artificial Intelligence Systems,” which are AI Systems that make “or [are] a substantial factor in making,” a Consequential Decision. A “Consequential Decision” is a “decision that has a material legal or similarly significant effect on the provision or denial to any consumer of, or the cost or terms of” opportunities or services in a variety of areas, including education, employment, finance, lending, essential government services, legal services, housing, health care or insurance.[16]

The Act then imposes significant disclosure obligations on developers and deployers of High-Risk AI Systems that meet this definition. Developers must provide deployers with “high level summaries of the type of data used to train [the system],” “known or reasonably foreseeable risks of algorithmic discrimination arising from intended uses”, evaluations and mitigation efforts regarding algorithmic discrimination, and other information needed for the deployer to satisfy its own obligations under the Act.[17] Developers may need to provide some of this information to the Attorney General and on their own websites. Additionally, they must make additional disclosures to their deployers and to the Attorney General in the event they learn of actual or reasonably foreseeable risks of algorithmic discrimination.[18] Deployers, in turn, must notify consumers of their use of High-Risk AI Systems, provide a plain language description of the system, and provide information about how their data is processed.[19] In the case of adverse decisions, they must provide a more detailed explanation, including the degree to which the system was used in the decision-making, the types of data processed, and the sources of those data.[20]

Importantly, the CAIA affirmatively addresses trade secrets. With respect to public disclosures, the act provides that developers cannot be required “to disclose a trade secret, information protected from disclosure by state or federal law, or information that would create a security risk to the developer.[21] Deployers likewise cannot be required “to disclose a trade secret or information protected from disclosure by state or federal law,” although they may be required to disclose that they are relying on this exception.[22] Deployers and developers may also designate information required to be disclosed to the Attorney General as proprietary or a trade secret.[23]

California’s AB-2013

Focusing on developers and their training data exclusively, California’s recently passed Generative Artificial Intelligence Training Data Transparency Act (“California Training Data Act”) reaches virtually all artificial intelligence systems,[24] and requires public disclosure of “documentation regarding the data used by the developer to train the generative artificial intelligence system.”[25] This disclosure must at least include “a high-level summary of the datasets used in the development of the generative artificial intelligence system or service,” addressing details that could constitute trade secrets, such as “[t]he number of data points included in the datasets, which may be in general ranges”; “[w]hether the datasets were purchased or licensed by the developer;” “[w]hether there was any cleaning, processing, or other modification to the datasets by the developer, including the intended purpose of those efforts in relation to the artificial intelligence system or service”, and more.[26]

The Act contains no exceptions or exclusions for information the developer might consider a trade secret, raising concerns for some. According to the Business Software Alliance,

As currently written, AB 2013 would essentially require developers of generative AI systems to post detailed documentation about how their systems are trained, potentially requiring companies to disclose trade secrets or confidential information….[27]

As they further argued, “requiring such detailed information about the datasets developers use to train AI systems may obligate companies to disclose trade secrets or other confidential information, which raises practical and competitive concerns.”[28]

What is a Trade Secret Holder to Do?

Compared to Colorado’s Act and its broad exclusion of trade secrets from its disclosure requirements, California’s Training Data Act is much more of a threat. It uses transparency itself as a goal to help regulators and the public learn about the data used to train AI systems and investigate it on their own, starting from the premise that harm has already occurred. The California Assembly Committee on Privacy and Consumer Protection argued that developers of existing systems “have cut corners, ignored corporate policies and debated bending the law”, and “have not hesitated to move fast and break things,” allegedly including illegally obtained (or, in the case of child pornography, simply illegal) materials in their training data sets.[29] The California Senate Judiciary Committee made similar points, finding that “[r]equiring transparency about the training data used for AI systems helps identify and mitigate biases, addressing hallucinations and other problematic outputs, and shines the light on various other issues, such as privacy and copyright concerns,” and cited academic research arguing for broad transparency as a way to uncover these issues.[30]

AI developers and deployers thus need to keep abreast of these and other regulatory efforts and should consider a trade secret audit to identify those aspects of their systems that are most important to protect.

[1] Several organizations track these efforts. See, e.g., Orrick AI Center, https://ai-law-center.orrick.com/; IAPP, US State AI Governance Legislation Tracker 2025, https://iapp.org/resources/article/us-state-ai-governance-legislation-tracker/.

[2] Artificial intelligence regulations distinguish “developers” or “providers” and “deployers.” The EU “AI Act” defines a “provider” as “a natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body that develops an AI system or a general-purpose AI model or that has an AI system or a general-purpose AI model developed and places it on the market or puts the AI system into service under its own name or trademark, whether for payment or free of charge,” and a “deployer” as “ a natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body using an AI system under its authority except where the AI system is used in the course of a personal non-professional activity.” Regulation (EU) 2024/1689, Articles 3(3) and 3(4). In other words, a “developer” creates the system, and a “deployer” offers the system to the public, often via a B2B, B2B2C, or SaaS business arrangement between the deployer and developer. This working paper will use the terms “developer” and “deployer.”

[3] California Civil Code § 3110 – 3111.

[4] See C.R.S. (Colorado Revised Statutes) § 6-1-1701 et seq.

[5] See, e.g., Sonia K. Katyal, Private Accountability in the Age of Artificial Intelligence, 66 UCLA L. Rev. 54 (2019).

[6] See Katyal, supra, at 105 (“As Danielle Keats Citron has noted in her foundational work on this topic, automated decisionmaking systems have become the primary decisionmakers for a host of government decisions, including Medicaid, child-support payments, airline travel, voter registration, and small business contracts.”) (citing Danielle Keats Citron, Technological Due Process, 85 Wash. U. L. Rev. 1249, 1252 & n.12 (2008)).

[7] See Matthew D’Amore, AI Regulation & Trade Secret Protection: Risks and Recent Examples, AIPLA 2024 Trade Secret Summit Working Paper (available from author).

[8] OECD AI Principle 1.3, Transparency & Explainability, Rationale (https://oecd.ai/en/dashboards/ai-principles/P7, retrieved on March 14, 2025). See also OECD, Recommendation of the Council on Artificial Intelligence, OECD/LEGAL/0449 (2025).

[9] Id.

[10] Id.

[11] Id.

[13] See https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/regulatory-framework-ai (last visited Mar. 17, 2025)

.

[14] See Gunashekar & Salil, Risk-Based AI Regulation: A Primer on the Artificial Intelligence Act of the European Union, RAND Corp. (Nov. 20, 2024), https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA3243-3.

[15] For a detailed summary of the CAIA, see Stuart D. Levi, Colorado’s Landmark AI Act: What Companies Need To Know, Insights | Skadden Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP (June 24, 2024), https://www.skadden.com/insights/publications/2024/06/colorados-landmark-ai-act.

[16] C.R.S. (Colorado Revised Statutes) 6-1-1701(2), (3), (9).

[17] Id. at 6-1-1702(2), (3).

[18] Id. at 6-1-1702(4), (5), (7).

[19] Id. at § 6-1-1703(4)(a).

[20] Id. at § 6-1-1703(4)(b).

[21] Id. at § 6-1-1702(6).

[22] Id. at § 6-1-1703(7), (8).

[23] Id. at 6-1-1702(7) (developers), -7103(9) (deployers).

[24] The California Training Data Act defines “artificial intelligence” as “an engineered or machine-based system that varies in its level of autonomy and that can, for explicit or implicit objectives, infer from the input it receives how to generate outputs that can influence physical or virtual environments.” Cal. Civ. Code. § 3110(a). The Act exempts from disclosure systems whose sole purpose relates to security or national airspace, or was developed for national security, military, or defense purposes and available only to federal entities. Id. at § 3111(b).

[25] Id. at § 3111.

[26] Id. at § 3111(a).

[27] BSA Raises Concerns Regarding Expansive California AB 2013, Bus. Software All. (Aug. 28, 2024), https://www.bsa.org/news-events/news/bsa-raises-concerns-regarding-expansive-california-ab-2013 .

[28] Letter from the Business Software Alliance to Assemblymember Jacqui Irwin, Aug. 1, 2024, available at https://www.bsa.org/files/policy-filings/08012024bsacaab2013.pdf (last visited March 18, 2025).

[29] California Assembly Committee on Privacy and Consumer Protection, April 30, 2024 Hearing Report, at 5-6.

[30] California Senate Judiciary Committee, June 25, 2024 Hearing Report, at 5-6.